STEM Career Connections

Meet Dr. Eric Lindstrom, Physical Oceanography Program Scientist

Job Title

Physical Oceanography Program Scientist

Dr. Eric Lindstrom

Work Description

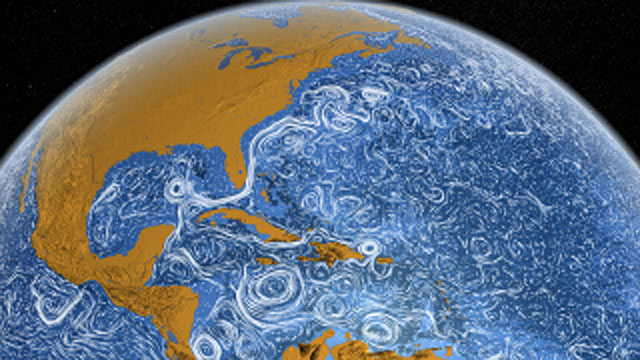

Dr. Eric Lindstrom is the Physical Oceanography Program Scientist in the Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington D.C. He is Program Scientist for the QuikSCAT, Jason-2, Jason-3, SWOT and Aquarius satellite missions and is the leader for the Earth Science Division Climate Focus Area. He has degrees in Earth and Planetary Sciences from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1977) and Physical Oceanography from the University of Washington (1983). His scientific interests include the circulation of the ocean and air-sea exchange processes and include extensive experience in both sea-going oceanography and remote sensing.

He is now serving as Co-chair of the international Global Ocean Observing System Steering Committee and Co-chair of the US Interagency Ocean Observations Committee (IOOC). Recently, as Chair of the Ocean Observation Panel for Climate he helped establish a web site of ocean climate indices and as co-chair of the Task Team for an Integrated Framework for Sustained Ocean Observations completed guidelines for system development entitled “The Framework for Ocean Observing (http://www.oceanobs09.net/foo/).

Eric Lindstrom is the recipient of the 2013 American Geophysical Union Ocean Sciences Award for leadership and service to the ocean science community.

Bio

In July 1969 I was watching Neil Armstrong take his first step on the moon at Tranquility Base, like everyone else with a TV at the time. I was at USC Wrigley Marine Center on Catalina Island as a 13-year-old visiting my brother, who was spending the summer studying there. If you had asked me then if I would wind up working for NASA, I would have said, “No, I’d rather pursue oceanography!” Well, since 1997 I have been the Physical Oceanography Program Scientist at NASA Headquarters AND I am a dedicated sea-going oceanographer. It stills feels kind of crazy what comes around in life. I write my short career biography here for students who may consider working in oceanography or for NASA or both.

After graduating from Huntington Beach High School in California in 1973, I took the train across the country to begin my college career at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. After only one semester of MIT physics and mathematics problem sets, this boy gravitated to the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences and asked them how I would train to be an oceanographer. There were no undergraduate oceanography courses, so I was told to take physics and math (ouch!) and to get my degree in Earth Science I would have to take the required geology and geophysics courses, too. I did all that, but rocks were not my first love. Luckily, a Professor of Physical Oceanography at MIT, John Bennett, allowed me to work with him under MIT’s Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program (UROP) and sit in on his graduate level physical oceanography courses. We worked together on an analysis of the coastal boundary layer in Lake Ontario, and I co-authored a paper with him that appeared in the Journal of Physical Oceanography in the summer of 1977. UROP and that research paper were a big boost for my applications to graduate school. I still donate money annually to MIT’s UROP to honor its impact.

For graduate school I sought out a diverse set of schools: UCSD Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of Washington, Princeton, and University of Miami. I was told that since I was at MIT, I should NOT apply to the MIT/Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution joint program (that was weird). In the end I did have choices and settled at University of Washington working with Professor Bruce Taft. It was the era of Apollo-Soyuz and USA-USSR cooperation in space and oceanography, so I embarked on studying eddies in the North Atlantic with a diverse set of US and USSR scientists. The project was called POLYMODE. It was a fun project with time at sea and lots of workshops and meetings, including a month in Moscow doing a data exchange. The connection to the space program was remote and programmatic and I hardly noticed it at the time. I received my PhD in September 1983, the day the Australian’s won the America’s Cup sailing race. I celebrated, since I had signed up to move to Australia to do oceanography (and get married!) the very next month.

Australia was a hoot! We moved to Hobart in Tasmania where the government was building a new marine science laboratory and eventually a new oceanographic research vessel as well. It was a growing field because 200-mile Exclusive Economic Zones had just been declared and Australia wanted to know all about the waters around the continent—good work for a newly minted oceanographer! The team in Hobart had me focus on the western tropical zone, including the Coral Sea, Solomon Sea, Bismarck Sea, and the circulation around Australia’s neighbor Papua New Guinea. Hardly anything was known so I worked with some of my buddies back in the USA on developing the Western Equatorial Pacific Ocean Circulation Study (WEPOCS). It was a great success! We named some new ocean currents and replaced some old stale ideas with some fresh perspective on the role of the western tropical Pacific in climate.

While in Australia in the 1980s I also became involved in the planning of a huge international experiment – the World Ocean Circulation Experiment (WOCE). My work on WOCE had the Australian government send me back to the USA to work at Texas A&M University, the U.S. WOCE Office. That certainly began returning my roots to US soil. After returning to Australia it was not long until headhunters from USA sought my return to work again in the USA at the project office in Boulder, Colorado, of the Coupled Ocean Atmosphere Response Experiment (COARE; an experiment just off the coast of Papua New Guinea). The family decision was to make a return to the USA permanent.

Boulder only lasted about 18 months and then I returned to WOCE work as U.S. WOCE Program Scientist in Washington, D.C., in 1992 as an employee of Texan A&M University but under the direction of five federal agencies (each providing 20 percent of my support). Gosh, the world is convoluted sometimes! That, for me, began “interagency cooperation” in oceanography for which I am still deeply involved. Broadly, the five agencies that fund global oceanography projects are the same now as they were then: NSF, NOAA, Navy, NASA, and Department of Energy.

Eventually, after five years working on WOCE and the new Global Ocean Observing System, I got a call from Bruce Douglas at NASA Headquarters. He was serving a stint as Physical Oceanography Program Scientist and asked me to interview as his replacement. NASA told me they were looking for someone who could integrate their oceanography (from space) into the federal family of oceanography agencies. Certainly, I had experience for that. However, I told them I had no particular experience with satellite oceanography. Their idea, and response at the time, was that they had plenty of satellite oceanographers at NASA but that it might be good for their leader to be someone who had “touched seawater” and was open to learning about the new tools for satellite oceanography. Wow, I said, you have found the right person!

So, here we are, after 20 years, I have learned my fair share of satellite oceanography and have thoroughly enjoyed NASA. I have molded NASA Physical Oceanography into a community that fully supports its satellite missions with appropriate science at sea. I hope I have helped to make satellites an everyday tool for oceanographers. The positive feedback from the community has been most humbling. I am very lucky indeed to have landed on my own Tranquility Base.

Multimedia Resources

The Upper Meter of the OceanNASA Professional Profile

For the last 20 years, Eric's primary job has been supporting NASA satellite missions related to measuring physical characteristics of the ocean (principally, temperature, salinity, sea level, and winds) and supporting the oceanographers that generate knowledge from such data. He is currently aboard the Research Vessel (R/V) Roger Revelle in the Pacific Ocean as part of the Salinity Processes in the Upper Ocean Regional Study-2 (SPURS-2) field campaign. SPURS is undertaking oceanographic field experiments to further understand the essential role of the ocean in the global water cycle using a plethora of oceanographic equipment and technology, including salinity-sensing satellites, research cruises, floats, drifters, autonomous gliders and moorings.

You can read more about SPURS field campaign through Eric’s Notes from the Field blogs.

Credit: NASA Earth Expedition